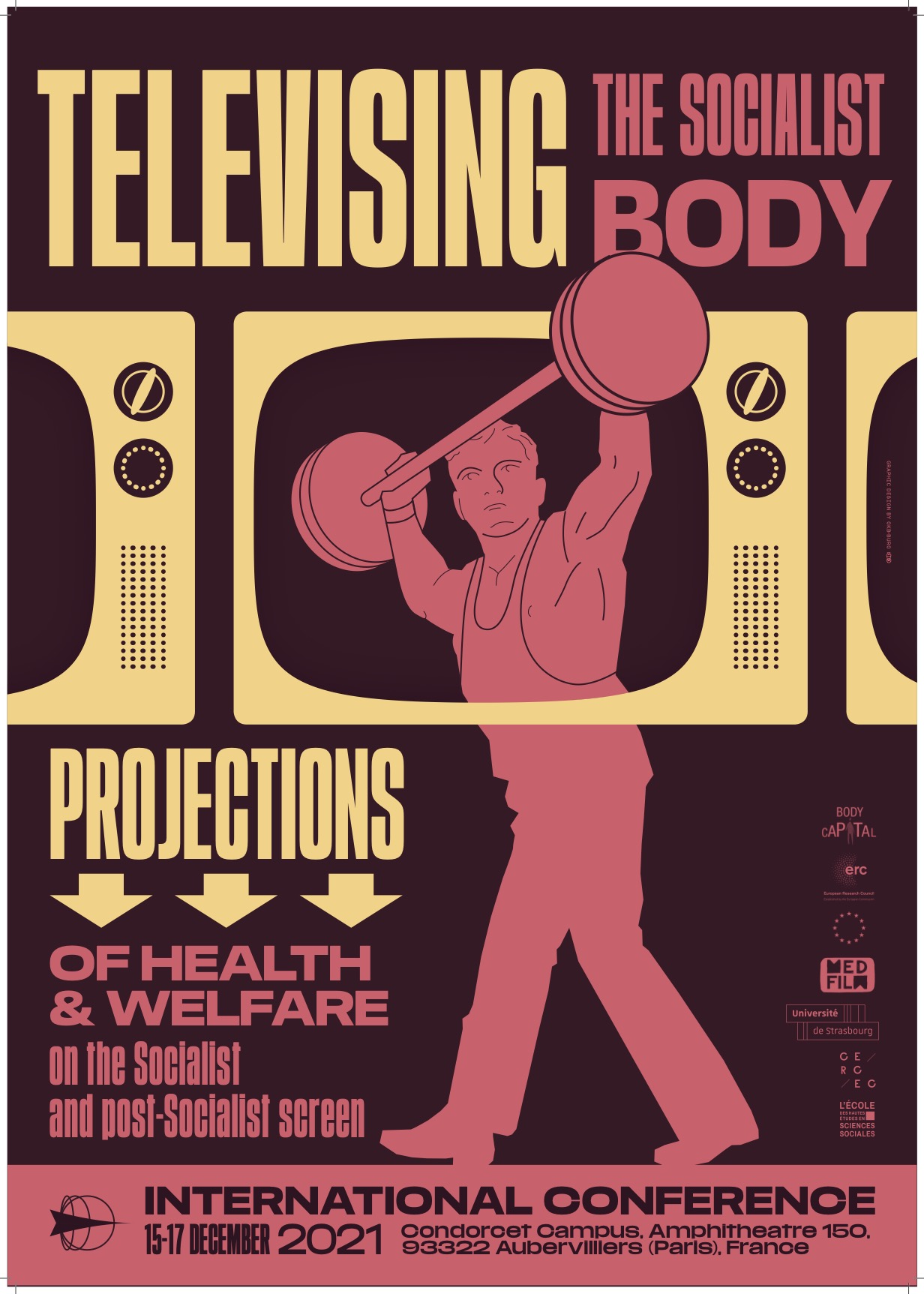

TELEVISING THE SOCIALIST BODY

Television prospered upon a tension between education and leisure, which was especially acute in a socialist context Televisions began to appear in homes in Eastern Europe after its stabilization as a socialist “block” dominated by the USSR. However diverse by nature and history, all the socialist regimes shared common strategies of mass propaganda, i.e. the intensive use of media to convert people and transform collective/individual behaviours. Televisionwas supposed to be a new tool allowing direct normative shaping of every citizen, but also blamed in some circles for stimulating the disarticulation of the class/work/political collective. Moreover, this tool was uneasy to master: the professionals trained to produce an efficient TV discourse mainly focused on socialist progress (i.e. omitting shortcomings and problems from the picture), and the spectators learned to read it (i.e. to select the information) at the very same time. Finally, crossed communication around programs helped the citizens to identify themselves with a Soviet way-of-life more “normal” than in the past 40 years.

The specificity of the Eastern case in the broader history of European television and the stakes of “socialist” body values merit both a nuanced assessment. The development of television coincided with a period in which ideas about the public’s health, the problems public health faced and the solutions that could be offered, were changing. The threat posed by infectious diseases and famines was receding, to be replaced by chronic diseases, which were linked to lifestyle and individual behaviour. Early in the 1920s’ Soviet Russia, and then on a large scale after World War II, the state turned into a welfare state. Lifelong medical care and social security were granted. In exchange citizens had to adopt new hygienic habits and healthy conduct: every citizen now had the right, and the duty, to be “healthful.” The state commissioned the educational institutions and the mass media to purge popular unscientific perceptions of medicine and impose an expert conception of the body. In Eastern Europe, the political power emphasized the necessity of a collective reshaping of the body, defining a “socialist” body (still to outline in general and in its national variations) that contrasted with its “corrupt” Western counterpart.

Watching TV in the 1950s-1990s was part of a shift towards more sedentary lifestyles, and also a vehicle through which products that were damaging to health, such as alcohol, cigarettes and unhealthy food, could be advertised to the public. In the Eastern part of Europe, where food was less scarce, alcohol and cigarettes affordable, the states endeavoured simultaneously to promote an ambiguous “socialist” well-being and fight the usual “social diseases”, encouraged consumption while condemning consumerism. Throughout the age of television, health and body-related subjects have been presented and diffused into the public sphere via a multitude of forms, ranging from short films in health education programmes to school television; from professional training videos to TV ads; from documentary and reality TV shows to TV news; but also, as complementary VHS and similar video formats. Spectators were invited not only to be TV consuming audiences, but also how shows and TV set-ups integrated and sometimes pretended to transform the viewer into a participant of the show. TV programmes spread the conviction that subjects had the ability to shape their own body.

Bodies and health on television have not been extensively researched, in particular in the socialist and transition to market-economy contexts. The conference seeks to analyse how television and its evolving formats—contemporary, similar and yet differing in national broadcast contexts—expressed and staged bodies and health from local, regional, national and international perspectives. The conference seeks to better understand the role that TV, as a modern visual mass media, has played in what may be cast as the transition from a national bio-political public health paradigm at the beginning of the twentieth century, to alternative societal forms of the late twentieth century when (supposedly) “better” and “healthier” lives were increasingly shaped by market forces.

We are looking to address such questions as (but not limited to):

How should we understand the relationship between TV and public health in a socialist and post-socialist context? Could we identify a common trend and transfers between televisions’ treatment of health in different socialist countries and contexts? What are the key changes and continuities over time and place? How does thinking about the relationship between public health and TV change our understanding of both? How were shifts in public health, problems, policies and practices represented on TV? How were institutions concerned with the public’s health presented – and staged – on TV broadcasts? How was TV used to improve or hinder public health? What aspects of public health were represented on TV, and what were not? In what way was TV different from other forms of mass media in relation to public health? How did the public respond to health messages on TV? To what extent can the notion of “market” be used in the socialist context to define the relationship between spectators/patients and television/doctors?

The conference aims to bring together scholars from different fields (such as, but not limited to, history, history of science, history of medicine, anthropology, sociology, communication, media and film studies, television studies) working on the history of television in East European countries and USSR/Russia in the post-Stalinist era and the years following the collapse of the Socialist Bloc. Papers might focus on one national, regional or even local framework, or may be comparative in approach. Indeed, considerations of the history of health-related (audio-) visuals as a history of transfer, as entangled history or with a comparative perspective inside the Socialist Bloc and/or with Western counterparts, are welcome. The organizers welcome contributions with a strong historical impetus from all social and cultural sciences.